Artists at Sundance are tapping into your own movements to make immersive experiences feel more natural.

Inside the softly glowing room, I pace around a table with an iPhone to reveal an augmented-reality mystery. Digital characters on my screen drop breadcrumbs for me to follow back to the scene of a murder. As I trace their trail of clues, my movements make everything around me change — the lights, the scenes, the sounds I hear in my ears.

The use of movement and location to direct the flow of the story is one of the key elements of The Dial, the brainchild of Peter Flaherty. While he wanted to incorporate augmented reality, which overlays digital media on top of the real world, and projection mapping, which shrink-wraps video onto physical objects, the most important technology for telling his story is one we’re already constantly using: our own bodies.

“The more your body’s engaged in any interactive or immersive form, the more meaningful it is,” Flaherty said in an interview at the Sundance Film Festival on the night before the fest opened late last month. “Those choose-your-own-adventures — where you choose A or B, pathway one or two — for me is never that exciting. But if you’re actually kinesthetically moving your body, you’re engaged.”

At the festival’s New Frontier showcase of tech-heavy immersive projects, pieces like The Dial are using participants’ bodies as the primary mechanism for how they work. Instead of bathing you in passive immersion or forcing fiddly game controllers into your hands, creators are nesting unfamiliar tech with an instrument — your body — that’s as familiar as the back of your hand. Literally.

Their hope is to make projects utilizing augmented and virtual reality — once hot tech trends still struggling to find their way to consumers — more engrossing. VR and AR could use all the help they can get to actually fulfill their promise of offering us radically different and immersive experiences. The trend could, at the same time, restore some of the connection we’ve lost to our physical selves that tech has cleaved away.

“It’s a critical moment culturally with the advent of spatial computing and the advent of also machine learning, for us … to put the body back at the center of the potential relationship of technology and humans,” said Melissa Painter, another creator whose project, Embody, is featured at Sundance. “Flat out, people’s physical relationship to their own body has somehow been stripped out of the equation.”

My technology, myself

Inside the glowing room-sized cube of The Dial, one viewer — dubbed the navigator — and two other people walk around a table with iPhones that reveal augmented-reality characters acting around a projection-mapped miniature house. The AR and projections reveal the characters and the sets, but the story’s scenes are unlocked depending on where the navigator decides to move.

It’s a little like walking in front of an automatic sliding door at a supermarket, except instead of opening the entrance to a store, you awaken a new scene to play out.

Your movements also sync with changing colors of light in this glowing cube. When you stand to the south of the miniature house, the lights turn pale blue to match the winter’s night setting of all the scenes that take place there. If you stand to the west of the house, the lights turn orange with long shadows to suggest the autumn afternoon.

The dial syncs lighting, AR scenes and projection mapping to a participant’s movements.

The Dial

All these high-tech orchestrations are designed to happen naturally as you follow whatever path through the story you want to take. Slowly, you unravel an interactive mystery centered on a woman who smashes through the stone wall outside her family home, exposing the underbelly of a formerly wealthy family.

Flaherty hoped that the end result would be an engrossing story that has an actual arc. Making movements central to the story would allow the interactive methodology starts to “disappear,” he said.

“They’re not focused on trying to break the tech, they’re not focused on trying to push the buttons,” Flaherty said of his hypothesis for the project.

Painter, on the other hand, purposely wanted to avoid telling a story with Embody, an experience that feels like going on a fantasy yoga retreat. (Note that even somebody like me, who is terrible at yoga, wanted to do it again.) Her design was to create something that felt like a product of the future rather than storytelling of the future.

Melissa Painter and her team created Embody to demonstrate novel ways technology can be used for physical wellness.

Embody

Experiencing Embody, you stand on a pressure-sensor mat in front of a stereoscopic camera that captures the shapes you make with your body. These capture data that helps sync the VR imagery taking place around you. Inside your headset, a translucent figure leads you through various body movements by example. As you mimic the move, animations of budding tree branches reach out to dance with you in rhythm with your own movements.

“We wanted to be able to use peoples’ bodies as the tool that piloted the experience but to take as much tech as possible off their physical bodies,” she said.

Your body, front and center

But a slew of projects at Sundance bring participant’s bodies to the fore.

Grissaille floats viewers through a virtual world created by artist Teek Mach before you enter a room where she paints the profile of your body using VR painting program Tilt Brush. Mach has spent more time in virtual reality in the last year than actual reality, experimenting with such things as going to bed in a headset so she would fall asleep and wake up in one of her Tilt Brush-created worlds.

Interlooped uses a technique called live volumetric capture to create a hologram of you and artist Maria Guta. You watch as Guta leads a stylized deconstructed version of you in real time through a trippy experiment. It’s among the first times that live volumetric capture for two people has been publicly executed.

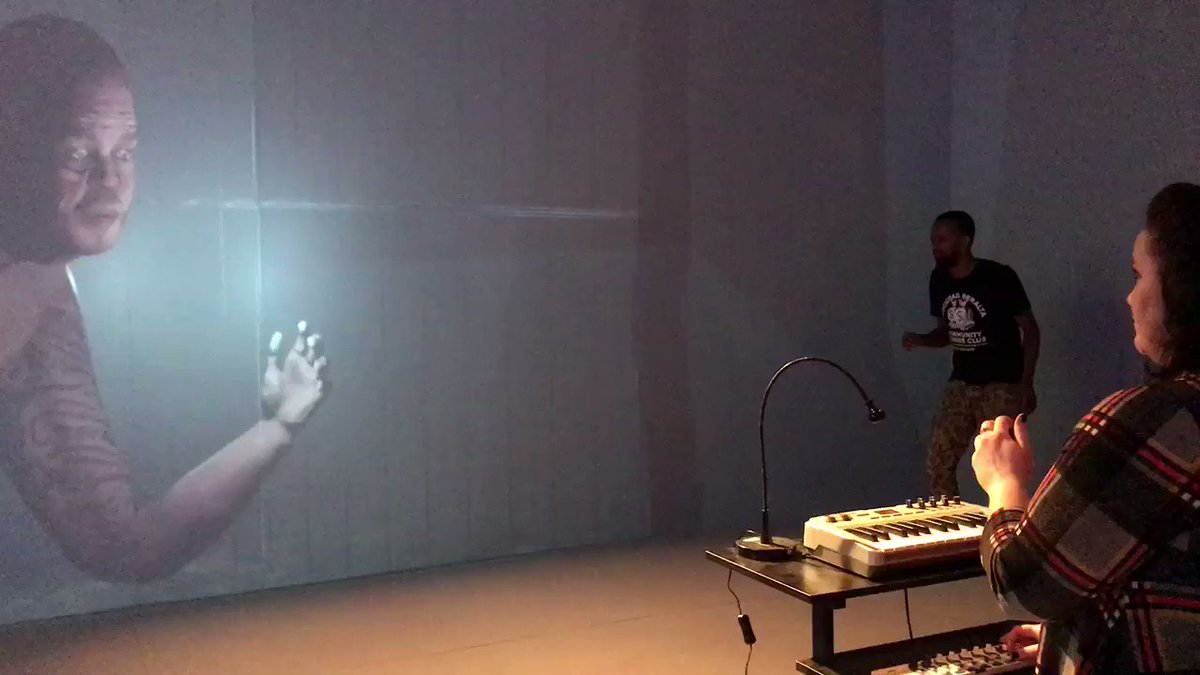

Esperpento uses actors’ bodies to puppeteer digital characters. The project, which includes a fictional dystopian world that is projected on two walls and a floor of a stage, also features a short play called Two Red Lights and One Black. In it, actors control parts of projected digital avatars with some body movements. When one woman gesticulates with her hand, the hand of a beefy prisoner projected on the wall moves in sync.

“I actually have recorded the show — every voice, what they do — and played it that way, and it’s not enough, it’s not the same,” said Victor Morales, the creator of the projector. “It’s really not about the technology or what the world is. But [it’s] the person who is playing the role, and how a game or a story can change depending on who plays it.”

This concept — of empowering and celebrating individuality with technology — carries a lot of weight for those critical of how the virtual, augmented and mixed reality technologies are being developed so far.

Painter said she’s concerned about the VR/AR/MR industry “driving toward oversimplification of what people do.”

“There’s too many people thinking about: If you can’t do it tomorrow in your living room, we shouldn’t be building it,” she said. “If we’re all leaning towards what we can push out the door tomorrow into a simplistic headset, we’re going to end up with nothing but zombie shooters.”

“To me, that’s not what this space is about,” she added. “It’s a chance to reset our relationship with technology.”

Source: www.cnet.com